Every person who ever lived wonders "where did I come from?" and the amazing thing is that until 1900 AD nobody knew. In ignorance, people lived with ideas that were fundamentally wrong.

And those ideas led to profoundly incorrect notions about the 'nature' of men, and the 'nature' of women.

-------------------------------------------------------

In the UK the book is available at the link below. Otherwise see Amazon USA, France, Spain, Germany or Italy.

Woman is the source of seed; man waters the seed

Societies that have left us the earliest examples of writing were in conflict between two reproduction theories: the father is the parent; and the mother is the parent. The further back in time you go, the stronger is the idea that women should be respected for their generative power. And when you go back so far there is no longer any written evidence, and look at the images left behind, it is pretty clear that people had this idea: the seed is in the woman and the man waters it. That reproduction theory would explain why there were so many 'earth goddesses' and 'thunder' or 'water gods'. Thunder is explosive, like ejaculation, and they both lead to a shower of liquid. And as any farmer knows, seeds need water.

Farming developed from gathering. People would collect wild grain - wheat or barley - and use it as food. Then they realised that the grain could be put in the ground to provide more plants, and more grain. This was a momentous discovery.

When they asked themselves 'where did the human seed come from?', the first most obvious answer would be the woman. After all, the 'plant' (the child) is pulled from the body of the woman.

In terms of one human controlling the other, this reproduction theory did not involve one gender controlling the other because the source of the seed, the woman, was the same physical person as the means of production (the woman). It was obvious that men were needed to water the seeds, but they were not parents as such.

Because seeds are singular - from one seed grows an entire plant laden with more seed - there was unlikely to be any speculation about two seeds and fusion.

Men helped, but mother was the source of life.

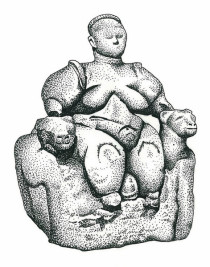

Catal Hoyuk Goddess 6,000-5,5000 BC, baked clay figurine, 20cm high (Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey)

Catal Hoyuk Goddess 6,000-5,5000 BC, baked clay figurine, 20cm high (Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey)

This figurine was found in a grain bin or, as I would call it, a seed store. It comes from a very important archaeological site in Turkey. Notice the two felines - probably leopards - on either side of her, looking very casual with their tails over her shoulders. This theme, of powerful women with two felines can be seen throughout the early Neolithic from India to Palestine, and beyond.

Also found here was a female figurine with a hole in her back through which you can still see a seed. It was placed low - about the level of the womb - and it

raises the question of how many other female figurines were made with seeds placed inside them but, because they're not damaged in the same way, we don't know the seed is

there.

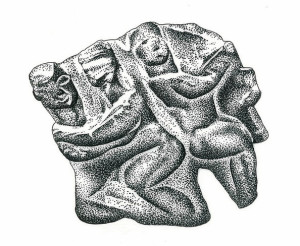

Catal Hoyuk Group, 6,000-5,500 BC, high-relief carving in stone, 11.6cm high (Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey)

Catal Hoyuk Group, 6,000-5,500 BC, high-relief carving in stone, 11.6cm high (Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, Ankara, Turkey)

Catal Hoyuk seems to have been an egalitarian society, both in terms of men and women, and in terms of there not being an upper class with palaces.

This stone carving is the first known that might illustrate where babies come from: it starts with an embrace on the left, and leads to a woman holding a baby on the right.

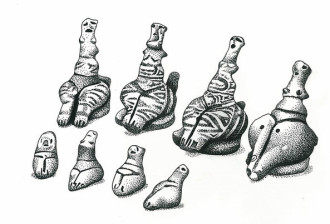

The Assembly of Snake Goddesses 4,800-4,600 BC. 21 figurines ranging from 6-12 cm high found stored in a large vessel at Poduri-Dealul Ghindaru, Romania (Piatra Neamt Museum, Moldavia, Romania).

The Assembly of Snake Goddesses 4,800-4,600 BC. 21 figurines ranging from 6-12 cm high found stored in a large vessel at Poduri-Dealul Ghindaru, Romania (Piatra Neamt Museum, Moldavia, Romania).

This picture shows a detail from a group of 7,000 year old figurines: 15 women, and 6 children. 13 of the women sit on chairs. They were all found together in a large vessel, stored there for safety. They have been called 'an assembly' or 'a council', but of course we have no idea what this scene was meant to represent. It does though seem they are engaged in a communal activity, presumably for the common good.

Impressive female figurines have been found all over the world. Archaeologists love to use the word "fertility" to descibe females - as if that word had any meaning. Do they mean "fertile" as you and I mean it (50% of the reproductive equation); or as patriarchs use it (good soil for the male seed to be planted it); or as the (100%) source of human life and perhaps all life, plant and animal - a goddess in the fuller sense of the word, like 'God'? But as archaeologists don't discuss reproduction theory, it's hard to work out what they do mean. If they even know.

If I sound annoyed that's because I have asked many archaeologists about their specialist areas: "where did they think babies come from?". And the disappointing thing is they have no idea what I am even asking.

The only reference archaeologists seem to make to reproduction theory is to say "men discoverd their role in reproduction around 10,000 BC." That is wrong by

12,000 years. What men discoverd in 10,000 BC was that they had A ROLE, which was a revolution at the time. But it wasn't THEIR role. Men only discoverd THEIR ROLE in 1900 AD. Before then everyone

was ignorant. So what did they discover? That is what archaeologists need to ask themselves. Can we have some clarity please?

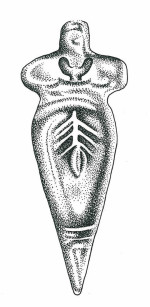

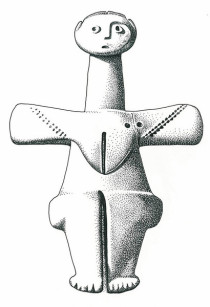

Cypress Goddess 3,000 BC, limestone figurines 39.5 cm high (J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California, USA).

Cypress Goddess 3,000 BC, limestone figurines 39.5 cm high (J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California, USA).

During the Neolithic people settled down and developed their local, individual, artistic and symbolic styles. This figurine from Cyprus is 16 inches high and,

as you can see, has a very well defined vulva at the breast level. But many figurines from Cyprus have, instead of a head, a phallus. This joining of the male and female is symbolic of the

relationship between men and women: one in which the water from the phallus stimulates the life-giving capacity of the female. It was a symbiotic relationship, where the male was valued. But the

central figure is female because she is 'mother' - the source of seed.

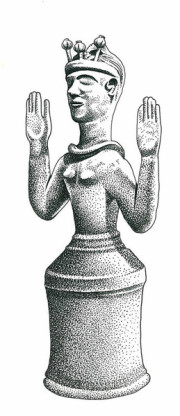

Crete Goddess/Priestess 1,350 BC clay figurine, post palatial, Gazi, Crete (Archaologischen Institut, Berlin, Germany).

Crete Goddess/Priestess 1,350 BC clay figurine, post palatial, Gazi, Crete (Archaologischen Institut, Berlin, Germany).

Not all female figurines are goddesses. This example from Crete is often referred to as a 'goddess' but I think she represents a priestess because she's wearing a head-dress make of opium poppies, which indicates she would use that drug to communicate with the diety. Also, many figurines simply represent ordinary women, perhaps women of status and power but, also, just regular women making a plea or a promise to the deity. In a sense, images of ordinary people placed in front of the image of a deity are them saying "look at me, here I am, I look like this, I dedicate myself to you, I am your servant, please help me". Votive figurines were common objects in earlier times.

But we will never get anywhere in deciphering the many Neolithic figurines until we can get our heads around the fact that people worshipped goddesses in the

very same way they have worshipped gods.

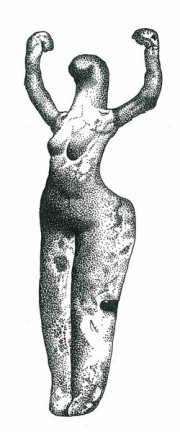

Egyptian Goddess, predynastic terracotta figurines with bird head and upraised arms (British Museum, London, England).

Egyptian Goddess, predynastic terracotta figurines with bird head and upraised arms (British Museum, London, England).

The head of this early Egyptian figurine is in the shape of a bird. Two animals often associated with goddesses were the snake and the bird. Snakes shed their entire skin and come out all new and shiny, as if reborn. People at this time didn't know, as we do, that birds migrate many thousands of miles. What they observed was that birds seem to disappear, then reappear as if reborn.

This association with rebirth is about life-after-death, which is a much deeper concept than "fertility".

The history of the phallus

A phallus can represent many things. It can represent sexual pleasure, or ritual defloration - the breaking of the hymen so babies can come out of the vagina. It can also represent 'reproduction', but what exactly do we mean by that?

Because archaeologists don't distinguish time in terms of reproduction theory, when they see a penis attached to a male figure they call him a "fertility god". That tells us nothing because the phallus has its own history and its meaning changed over time, for example:

- During Roman times a phallus represented the delivery of the male seed - 100% of the 'seed' or, as we would call it, genetic material.

- During the early Neolithic, when farming began, a phallus represented the delivery of water, irrigation, so the crops could grow and the seeds inside women could germinate and grow.

Some gods are so old they seem to traverse these two eras, their phallus once representing water, but coming to mean 'seed'. The Sumerian god Enki and the Egyptian god Min are examples.

The existence of phallic shaped objects, attached to figures of males or not, should not automatically be assumed to represent the idea that men are generants

or fathers. Before 10,000 BC the phallus is conspicuous by its absence. Then it bursts on the scene - in eastern Turkey. Of course men were delighted to find they had something to do with

reproduction, even if it was just helping to germinate the seed inside the woman. This was a revolution in terms of reproduction theory and it replaced the earlier notion - that women reproduced

entirely on their own.